ZLO

🇨🇿 Pátá výstava v sérii „Katastrofická sezóna“ nese kontroverzní název „ZLO“. Tento krátký jednoslabičný výkřik působí jako nečekaný průstřel srdeční komory, jehož fatálnost si plně uvědomíme až na prahu vlastního skonu. „Zlo“ je nenáviděné a tabuizované slovo. Proč nás jeho vyřčení tolik rozrušuje? Špatnost, nesvár, zášť, agrese – domníváme se, že nic z toho se nás osobně netýká, ale není zrovna pod naším svícnem ta největší tma? Expozice Danta Daniela Hartla kombinuje prvky dekadence, morbidnosti a horroru s mánickou euforií, zářivou teatrálností a nekorektním humorem, čímž staví most mezi psychotickou hrůzou a líbivou okázalostí. Leč i celá naše společnost trpí bipolární poruchou, kdy došlo k rychlému vědecko-technologickému pokroku, zatímco morálně a intelektuálně stagnujeme.

Zlo je tabu, a tabu vždy přitahuje. Umělec využívá faktu, že existence jakýchkoliv morálních zásad nás vždy bude vábit k jejich porušení coby zakázané biblické jablko. Nastoluje skandální otázku, zda zlo a egoismus nejsou nejvyšší formou svobody jedince. Německý filozof, Max Stirner, by s touto hříšnou myšlenkou za zvolání „Štěstí lidu je mé neštěstí!“ dozajista souhlasil. Autor se rovněž inspiruje existencialismem Alberta Camuse a ve svých dílech poukazuje na absurditu našeho bezúčelného bytí. Místo toho, abychom dali životu nějaký smysl a představili si Sisyfa šťastného, propadáme do chiméry konzumerismu a limbu lživého „amerického snu“, z něhož už se možná nikdy neprobudíme.

Kýčovitá oslnivost podbízivých reklam a morbidní vizualita manipulativní televizní zábavy metabolizovala ve společenskou dekadenci, kterou Hartl konfrontuje s dekadencí estetickou. Ošklivost už není dostatečně ošklivá – nahradila ji zdeformovaná krása. Ostatně ani ohavnost hrbatého kulhavého starce není zdaleka tak repulzivní jako ohyzdnost dříve krásné dívky proměněné v narkomanku prodávající své tělo. Nejedná se tedy o maximalizaci ošklivosti, nýbrž o její rafinovanou kombinaci se zdeviovanou krásou. V reakci na kulturní vyprázdněnost se u autora místo Kierkegaardova „Rytíře víry“ dočkáme apokalyptického „Rytíře ateismu“, kdy stav melancholie a nihilismu nepřechází ve víru v Boha (jehož Nietzsche ve své knize „Radostná věda“ nadobro pohřbil), nýbrž k „finis ultimus“ konzumu coby novému druhu fetiše a vanitas. Spatřiv, jak současný „homo oeconomicus“ involučně degraduje na „homo degeneratus“, Hartl přestřihává u časované bomby naráz oba dva drátky.

Přítomné objekty obklopuje aura bezčasí. Vše je zmraženo v prostoru, jakoby mrtvé či katalepticky strnulé v tetanovém spasmatu. Nelze se ubránit dojmu, že vystavené výtvory mají své vlastní vědomí, život, lidskou duši a s ní i ontologické „Dasein“, jež s námi sdílí. Nemůže tomu být ani jinak, neboť každý autor vkládá do svých výtvorů část svého ducha a vůle, stávaje se součástí svého díla ve formě individuálního panteismu. Cožpak není umělec božským demiurgem a zároveň i miltonovským Satanem vlastního tvůrčího univerza? A kdo by chtěl být Bohem, když může být Ďáblem? Však i Charles Baudelaire prohlásil, že ctnost je umělá a nepřirozená, zatímco zlo se páše bez námahy.

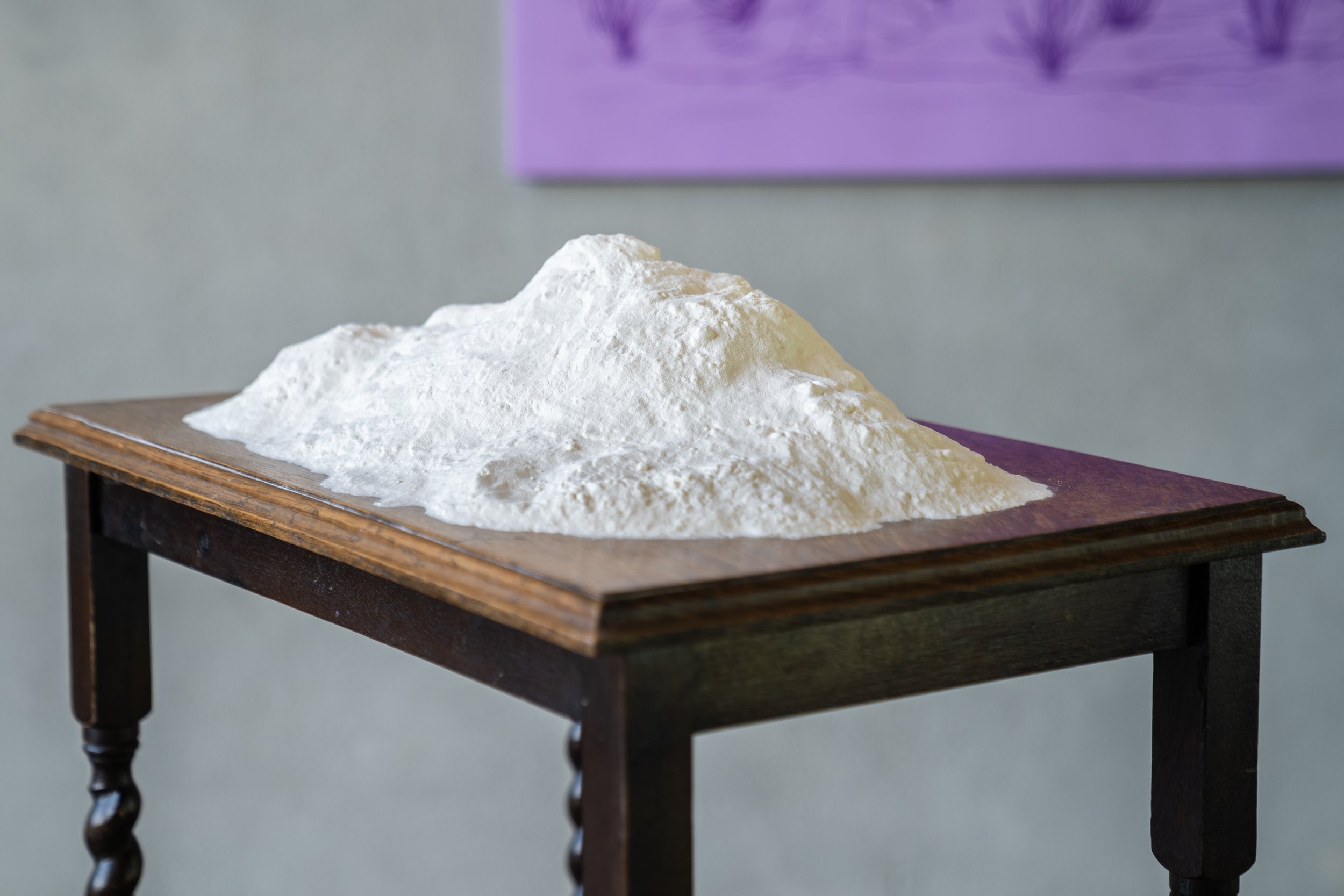

Promyšlená konceptuální provokace, kterou bychom nalezli i v tvorbě jiných dekadentních sochařů typu Hanse Bellmera či bratrů Chapmanových, je častým leitmotivem Hartlových děl. Např. asambláže ze série „Crime Scene“ přináší svědectví z míst po spáchaných zločinech. Není tam žádná krev či stopy po násilí, takže je jen na nás, zda se odvážíme rekonstruovat si tragédii ve své mysli, či se budeme pouze kochat informelní estetikou bez dalších konotací. K zamyšlení podněcuje i dílo „Human Strain“, neboť při pohledu na stůl coby kus nábytku si obvykle nepředstavíme nic negativního, avšak lidská lebka nahrazující část jeho nohy nás zde značně vyvádí z míry. Dojdeme k prozření, že stůl může být použit nejen jako jídelní a pracovní, ale i operační a pitevní. Francouzský básník, Comte de Lautréamont, charakterizoval moderní krásu jako „náhodné setkání šicího stroje a deštníku na pitevním stole“. V umění ale nic není náhoda – náhodný je pouze náš bolestiplný lidský život. Na to konto Otto M. Urban konstatoval, že „bolest a utrpení vede k novému prozření“.

Tam, kde pokrytecká společnost s fanglemi a duhovými transparenty vítá ekonomické migranty, aktivisticky se přivazuje ke stromům a pořádá pochody na podporu nejrůznějších sexuálních menšin, cynik Hartl vztyčuje prapor s nápisem „ZLO“ coby kritický vykřičník, jímž nás probouzí z halucinace falešného klidu a iluzorního blahobytu. Kéž je tento ironický manifest „le mal pour le mal“ varovným zvonobitím pro naši hroutící se societu, jež může brzy následovat osud starého Říma. Na této výstavě zkřížila umělecká dekadence meč s dekadencí společenskou. Čas ukáže, kdo z tohoto boje vzejde jako vítěz.

Kamil Princ

kurátor výstavy

🇬🇧 The fifth exhibition in the "Catastrophic Season" series bears the controversial title "EVIL". Usually, "evil" is perceived as a detested, and even an offensive word. Why does this term upset us so much? Wickedness, discord, resentment, aggression – we believe that none of this applies to us personally, but isn't the greatest darkness right under our candlestick? Dante Daniel Hartl's exposition combines the elements of the decadent, macabre and morose with an eccentric euphoria, radiant theatricality and wry humor, bridging the abyss between inward dread and pleasurable flamboyance. Actually, our entire society suffers from bipolar disorder, where there has been rapid scientific-technological progress while we are morally and intellectually stagnant.

Evil is taboo, and taboo always attracts. The artist (ab)uses the fact that the existence of any moral principles always invites us to violate them as a forbidden fruit. It raises the scandalous question of whether evil and egoism are not the highest form of individual freedom. The German philosopher, Max Stirner, with his sinful quote "The people's good fortune is my misfortune!" would certainly agree. The author is also inspired by the existentialism of Albert Camus and points out the absurdity of our aimless being in his works. Instead of giving life some meaning and imagining Sisyphus happy, we fall into the chimera of consumerism and the slumber of the false "American dream", from which we may never wake up.

The kitschy glare of condescending advertisements and the morbid visuality of manipulative television entertainment have metabolized into the social decadence, which Hartl confronts with his aesthetic decadence. Ugliness is no longer ugly enough – it has been replaced by distorted beauty. After all, even the hideousness of a hunchbacked, limping old man is nowhere near as repulsive as the odiousness of a formerly beautiful girl turned into a drug addict prostitute. Thus, this axiological view is not about maximizing ugliness, but about its refined combination with deviant beauty. In response to the cultural emptiness, instead of Kierkegaard's "Knight of Faith", we see an apocalyptic "Knight of Atheism", when the stage of melancholy and nihilism did not develop into the faith in God (whom Nietzsche killed for good in his book "The Gay Science"), but to the "finis ultimus" of consumption as the new kind of fetish and vanitas. Seeing how the current "homo oeconomicus" involuntarily degrades into "homo degeneratus", Hartl cuts both wires of the time bomb.

The presented objects are surrounded by an aura of timelessness. Everything is frozen in space, as if being dead or cataleptically stiff in a tetanic spasm. One cannot avoid the impression that the exhibited art pieces have their own consciousness, inner life and soul together with the ontological "Dasein", which they share with us. It cannot be otherwise, since every artist inserts a fragment of his will and spirit into his creations, becoming a part of his own work in a form of individual pantheism. Isn't the artist the divine Demiurge and at the same time the Miltonian Satan of his own originative universe? And who would want to be God when he can be the Devil? Even Charles Baudelaire declared that “virtue is artificial, while evil is natural.”

Thoughtful conceptual provocation, which we would also find in the work of the decadent sculptors such as Hans Bellmer or the Chapman brothers, is a frequent leitmotif of Hartl's creative process. For instance, the assemblages from the "Crime Scene" series bring testimony from places where atrocities have been committed. There is no blood or traces of violence, therefore, it is up to us whether we dare to reconstruct the tragedy in our minds, or just enjoy the indefinite aesthetics without other connotations. The work "Human Strain" is also thought-provoking, since when we look at a table as a piece of furniture, we usually don't imagine anything negative, however, the human skull replacing a part of its leg heavily upsets us. We reach the revelation that the table can be used not only for dining and working, but also for surgery and dissection. The French poet, Comte de Lautréamont, characterized modern beauty as "the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table". Though, nothing in art is a mere coincidence – the only truly accidental thing is our painful human existence. On this account, the art historian, Otto M. Urban, stated that "pain and suffering leads to new insight". A bad event can become a good thing in the end.

Where our hypocritical society armed with rainbow banners welcomes illegal migrants, activists tie themselves to trees and organize bizarre pride marches, Hartl cynically raises a flag with the inscription "EVIL" as a critical exclamation point, through which he awakens us from the hallucination of false calm and illusory welfare. Let this ironic manifesto "le mal pour le mal" be the warning bell to our collapsing society, which may soon follow the ill fate of ancient Rome. At this exhibition, the artistic decadence crosses swords with the social decadence. Only time will tell who will emerge from this fight as victorious.

Kamil Princ

exhibition curator